Off our kitchen is an open-air utility room. On the right side of this room is a back door, the live-in’s entrance. Opposite this door, left of the kitchen, is a tiny room that’s intended to house a live-in. The live-in is usually a domestic helper, although one of the families in the building has a live-in male driver and also a live-in helper—and two children as well, so I’m curious how four adults and two kids share the same amount of space that sometimes makes David and me feel crowded. How they manage in such close quarters is absolutely none of my business—but really, who wouldn’t want to know?

The live-in’s room is large enough for a single cot. Beyond the room is a cramped bathroom with an undersized sink mounted in the corner, a toilet that’s half the size of the others in the flat, and a plastic nozzle hooked to the wall at waist-height—not a proper shower at all. We use this bedroom and bathroom for storage. I’ve never considered having a live-in because I prefer only the people who love me to have a close-up of my imperfections. I drink too much, eat too much, play too much spider solitaire—why would I want an outsider watching me? I’m not the only one who feels this way. I have a friend who, when she’s going to play bridge, tells her helper that she’s going to a charity meeting. “I want her to think I’m doing important things,” my friend says. “I don’t want her to know I’m spending the entire afternoon playing a game.”

Rumors about the live-ins abound in the ex-pat community. The most common is how the ex-pat wife takes the kids back home for the summer, leaving her husband in the care of the domestic helper; and during the wife’s absence, the helper makes a move on the husband. This is an oft-repeated story, intended as a warning among friends—and though I’ve met people who know people who know someone it’s happened to, I have yet to actually meet anyone whose marriage has been endangered in this way.

Another tale that’s been making the rounds ever since I got here is the one about the vindictive cleaner. In Singapore a live-in must have a sponsor—someone who provides a home and regular employment. The live-in must not work for anyone but this sponsor and, likewise, it’s against the rules to hire someone whom you’re not sponsoring, which leads to the scary story of how, when an under-the-table cleaner was let go because the woman she was working for on a part-time basis found someone cheaper, the one who’d been let go turned her ex-employer in to the authorities—and no one wants to get on the wrong side of the Ministry of Manpower. I’ve heard this account from four difference sources. How much retelling is required before a story becomes urban legend?

Another story that flows from mouth-to-ear and mouth-to-ear is the one about the live-in who’d been working here for five years, sending money back to the Philippines to support her husband and children. When she went home for a visit, she discovered that her husband had dumped the kids with her parents and taken a mistress. A sizeable portion of the live-in’s earnings had gone to support the mistress. This story has a different slant in that the victim is the Filipina. As far as I can see, there’s no reason why this teapot drama is so popular among the ex-pat women, except that they seem to find malicious satisfaction in telling it, which I find puzzling.

Live-ins are a colorful and ubiquitous entity. They’re in front and behind me in the grocery store line. They’re up and down the street constantly, walking the dogs. They take toddlers to the pre-school at the bottom of the hill and fetch them home again three hours later. Some smile and some are surly. Some like the people they work for and some don’t. They all have people back home that they miss. And they all need the money they earn working far from their families.

This is Mary, the live-in from the seventeenth floor.

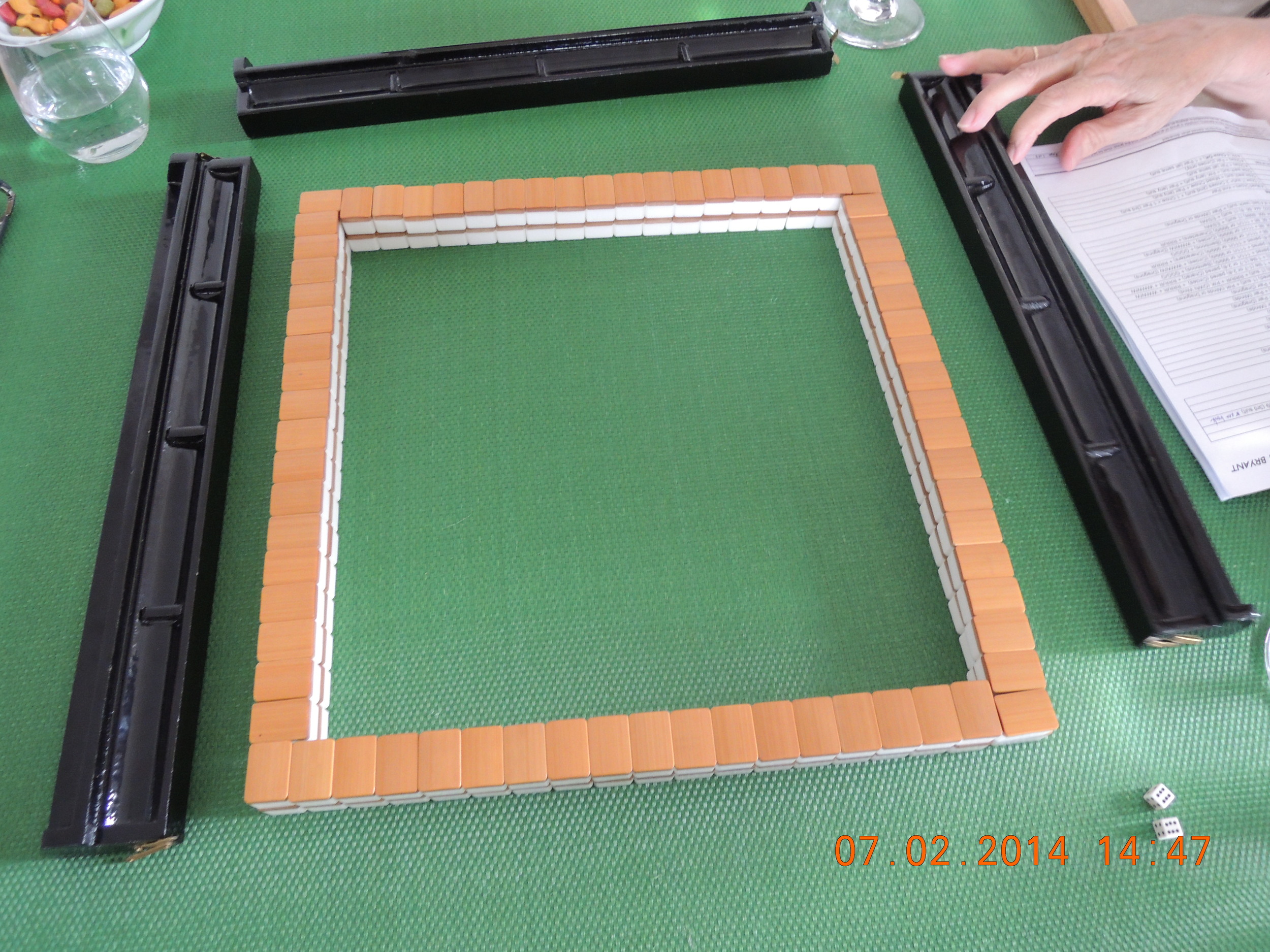

This is the space that's intended for the live-in.

Carrying the groceries up the hill from the grocery store.

On Sundays the domestic helpers meet their friends on Orchard Road.

This picture of me playing with Trip has nothing to do with the posting--but I thought it was funny that I'm squatting like the wiry street workers do when they're on break. Can you squat like this?