Last time I was at the Grand Palace, acceptable attire for women was cropped jeans and a wrap to cover bare shoulders. I looked it up before I dragged Resi and Georgia here, just to be sure—and the website I found indicated that nothing has changed. But when we get here a little man judges Georgia and I to be not quite decent enough. Georgia’s pants show two inches too much calf, and our thin shawls simply won’t conceal our exquisite pearly shoulders. He waves us over to the side, to the line where, for only a two hundred Baht deposit, we’re able to borrow shirts for both of us and a wrap-around skirt for Georgia.

We accept the articles and are shown to a changing room, where an electric fan is aimed into a low corner, where its breeze is not needed. The place where it should be aimed is at me. I reach out to adjust the fan, but the spaces between the wires of the guard are wider than I expect, and my thumb goes right through, catching the plastic blade of the fan and breaking it, causing an awful racket as the busted blade clatters round and round inside its cage. I inspect my thumb—no damage. The fan dies and silence prevails. I’ve caused great consternation for the attendant, who calls her boss, who must call her boss. I stand, pointing foolishly at the fan, telling them I’m sorry, but really, what good was it if it wasn’t pointed where it was needed? The woman in charge is reluctant to let me leave, but I remind her that I’ll be back through to get my deposit, and we can settle it then. I’m certain they’ll make me pay to replace it, which is fair. I’m just glad I still have my thumb.

The heat hits Georgia hard. Wearing two layers of cotton, the top layer heavy and impermeable, she’s red-faced and dripping before we even enter the temple area, too miserable to appreciate the history and magnificence of the colorful temples. (Inserting my opinion—burdened by an overwhelmed infrastructure, Bangkok does an extraordinary job of caring for its main attraction. The pavements of the Grand Palace are spotless, the reflective surfaces of the elaborate spires twinkle, brightly clean; and the renovation work, which is ongoing, is unobtrusive and reveals dedication and generous funding.) Resi, too, is suffering. Hot and exhausted, her knees are hurting, and every other step involves an up or down stair.

I persevere. I don’t make them walk the whole thing, but they must halt their wretched huffing and whimpering for a minute and recognize where they are, the grandeur that’s before them. I think, by the time I allow them to leave the Grand Palace, they hate me a little for subjecting them to this hell, blaming me for the scorching sun, the sapping humidity, the pressing crowds, and even the long trains of puzzled children with matching shirts who must all hold hands so they won’t be separated—and so we must wait for the kids to pass, the hot sun beating on our vulnerable pale heads as their headcount shuffles on and on and through.

At the exit we return our covering-clothes. My strategy of going unnoticed by keeping my head down works. No one realizes I am the miscreant who destroyed their fan. Should I alert them? Absolutely. But I’d rather not mess with it. I do get pretty tickled, though, when Georgia tries to reclaim our deposit. As she’s the one who paid and signed the form, she’s the one who must retrieve it. But her check-out signature doesn’t match her check-in signature. The man is confounded by her jagged scrawl. He compares. He dons glasses. He points to the first signature, points to the second, shakes his head. Overheated tourists form a line behind us. Georgia and I exchange looks. We are amazed that he is amazed. What does he see? It looks hunky-dory to us. He makes her sign again, compares signatures once more, then reluctantly returns her money, still shaking his head. On the way out I tell her I’m mortified to be associated with someone with an inconsistent signature.

Next up, a treat. We will not walk to the Reclining Buddha, we will grab a tuk-tuk, which Resi and Georgia haven’t ridden yet, and which I know they will enjoy. We fly, the breeze refreshing, the bumpy speed making us all laugh. We’re delivered to the gate. I promise them we won’t spend much time here. I’ve heard many people say that the Reclining Buddha is their favorite and I want to know why. For a hundred Baht we make our way to the door of the temple, take off our shoes, and enter. I’m not disappointed. There he is, mighty and huge in his golden splendor, a joyful relaxed giant, offering a contagious serenity which I appreciate after our tense time at the Grand Palace. Now I understand why so many like this guy who’s abandoned his chores and stress in order to indulge in a midday rest. The Reclining Buddha is now my favorite, too.

We take a tuk-tuk back to Khaosan Road, to the hotel, where we shower and put on fresh clothes. Georgia, who claims she’s never sweated this much in her life, is so impressed that she takes a picture of her sopping clothes.

Grace and beauty everywhere you look in the Grand Palace

There are several of these guys, keeping watch. Isn't he gorgeous?

Georgia and Resi. Can you tell how miserable they are?

This doesn't do justice to the Reclining Buddha. He's magnificent.

Georgia's happiest when she's making a new friend.

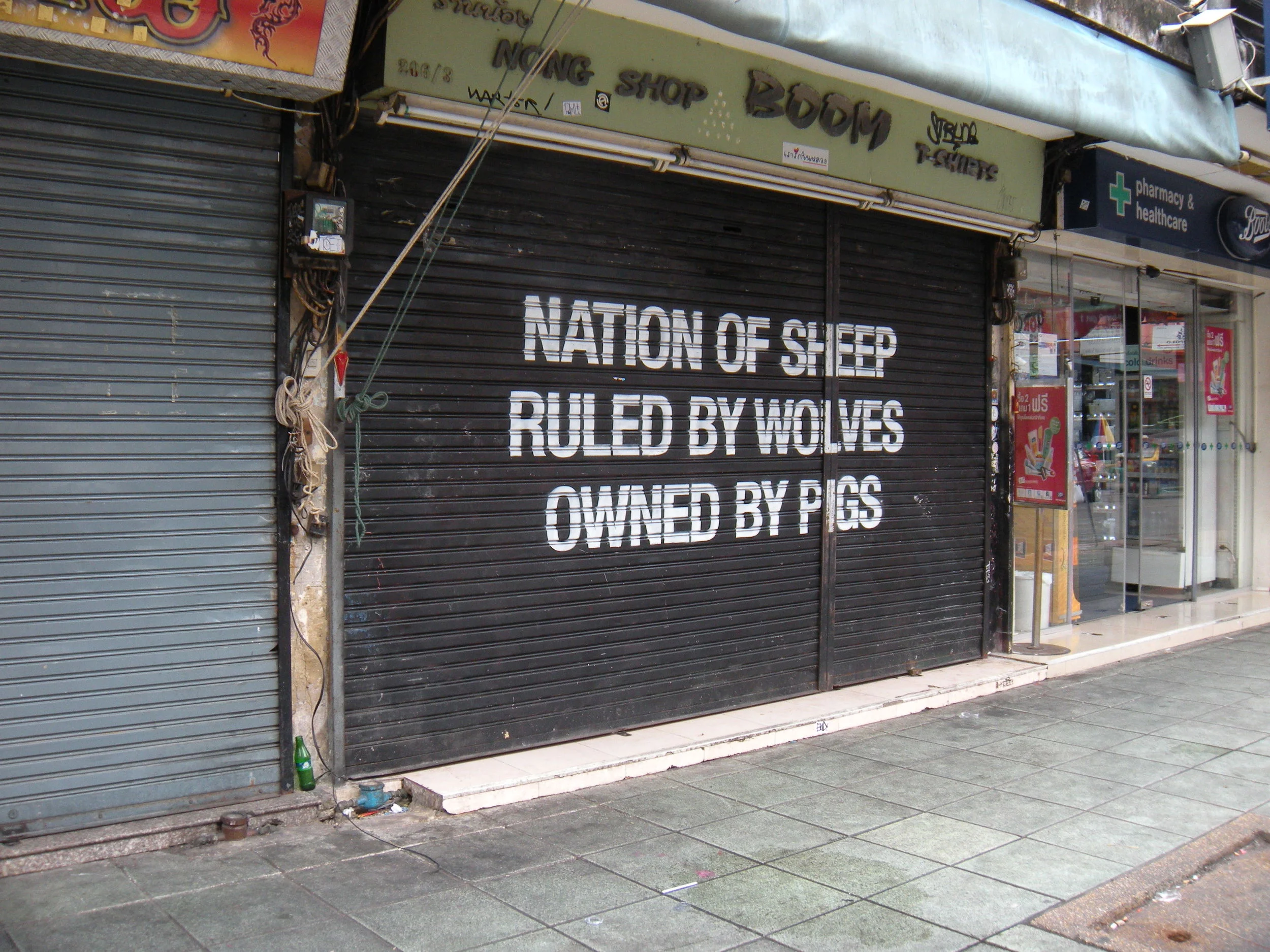

Though there's been recent unrest in Thailand, this sign on Khaosan Road was the only evidence of discontent that we saw.