When I was in seventh grade two girls phoned me within a space of fifteen minutes and tried to get me to say nasty things about one to the other. As neither had ever been particularly friendly toward me, I caught on right away. I imagined them in one of their bedrooms, eyes glittering with malice, as they clumsily tried to trick me. I avoided the mean-girls trap, but it didn’t make any difference. When I got to school the next day they’d passed it around that I’d said awful things about them.

Why, to any of this? I was a quiet girl, inoffensive, standing out in no way. This is only one of many instances I can recall from a lifetime of being blind-sided by the way people treat each other.

And the reason why it’s come to mind recently is that a neighbor couple is giving us the silent treatment.

Having lived with a father who would get mad and cold-shoulder a person, even his young daughter, for weeks at a time, I am fully aware of and impervious to this form of manipulation. I began to suspect the disintegration of the relationship with our neighbors back in November when the wife’s responses to my texts became terse. A message that used to contain emojis and exclamation points now only contained a brief word. A couple of invitations to come over for a wine and snack evening were turned down with no excuse. The husband no longer wanted to play golf with David.

Having learned how to handle my anger from my father, when David and I first began living together I used the silent tactic on him when he didn’t do what I wanted. During one of my icy pouts, he spoke to me as though I were an adult, though I was acting like a child, telling me that in our relationship we would talk about our issues, not stew over them. I will be grateful forever to him for teaching me that there are better ways to deal with bad feelings. Think how unhappy our marriage would have been if I had persisted in nurturing anger instead of talking things out.

“You know why I think they’re mad?” David asks.

“Why?” We’re at the local winery, picking up the three bottles of wine that our membership entitles us to. Joining a winery is an iffy concept. The wine isn’t good and it costs too much, but the surroundings are lovely and the ambience is convivial. Our sulking neighbors are here, too, carefully not looking toward us, not acknowledging us in any way. They’re laughing in the middle of a group of friends (be aware, friends; they’ll cut you off, too), and I think about how nice David and I are, and how much energy it must take to dislike us.

“Because you had Trip put down.”

This gives me pause. It’s true, they love dogs. They volunteer at the no-kill shelter, they have several rescue dogs, and they drive all over Texas delivering needy dogs to new homes.

“You think?”

“Look at the timing. They quit talking to us right after that.”

Trip had an eye infection that wasn’t responding to treatment. The vet said it was an inevitability that the infection would go to his brain, and that the only way to save his life was to take out his eyes. I considered it. It was a heart-crushing decision. He was deaf and blind. He was scared and lost all the time. And then to maim him in that way. I had him put down. That was two months ago, and I’m still lonely for my little dog.

“It hurts that someone would judge me for that,” I say, truly shattered. “And now, when I see them on the street, or driving past, it’ll make me relive losing Trip all over again; and I’ll think how, not only do I not have my dog, but I’ve lost friends over it.”

“Friends are people who talk to you, not people who don’t talk to you. Anyway, you have other friends—and every one of them thought you did the right thing.”

“Should we ask one of the neighbors to intercede? If they understood the situation, maybe they’d get over it.”

“Why release any more negativity into the cul-de-sac? Let’s just chalk it up to a lesson learned. We shouldn’t have gotten close in the first place.”

This is a truism most Americans would know, but because we’ve lived overseas for most of our adult years, we don’t understand the nuances. That’s not to say other places are different, because they’re not. Singapore, Holland, Scotland, Kuwait, London—in all the places we’ve lived neighbors sensibly maintain a distance. Here, in Marble Falls, we haven’t been sensible. For some reason we thought that, once we settled into a home in the US, we’d actually get to know our neighbors instead of exchanging impersonal nods in the elevator or waves from the driveway. Ex-pats have a tendency to romanticize home, to forget that we’re not all of the same mind, and that every person who’s friendly isn’t our friend. We’ve been naïve.

“I simply can’t be bothered to care anymore,” I say on a sigh.

“Life’s too short,” David agrees.

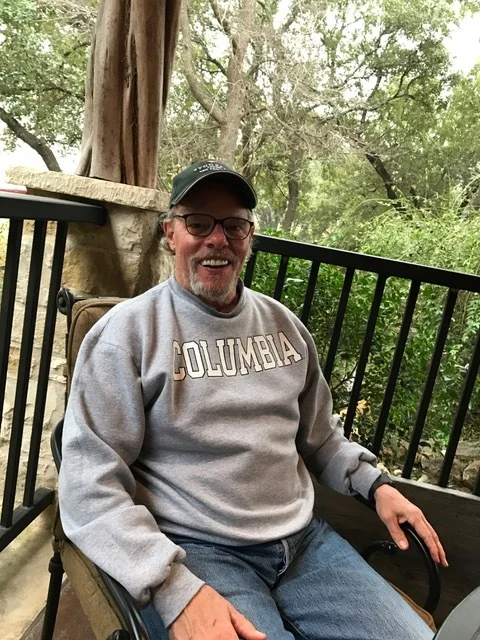

David's enjoying a Saturday afternoon at the winery.

It's a nice place to hang out, but the wine that they're so proud of makes my mouth pucker.