From a young age, the boys eschewed Sunday school. They thought the other children were undisciplined and that the teachers were disorganized. We didn’t push it, and as long as they were well-mannered, they were welcome to sit with us.

When we moved to Sugar Land from Scotland, and when the time was right, I looked up the Sunday schedule at the nearest Episcopal church. We arrived a little before the service in order to settle in and get a sense of the ambience.

The aisles divided the sanctuary into quadrants and, after a quick scan, the four of us decided on a pew near the front on the left side. We trooped in that direction. The ceilings were high and they had modern sound equipment—big screens mounted at the front and an elevated stage for the musicians.

As the minutes passed, more and more people came in until there was not a vacant seat. David, Curtis, Sam, and I were sandwiched in the center of the fourth pew. The service started normally—a song, a joyful prayer, and then the readings.

Unbeknownst to us, however, was that this service with its impressive crowd represented the reopening of the church, which had been closed for several weeks. The reason for the closure became clear when the priest took the pulpit.

“What you, as a church, have gone through is nothing short of tragic.”

This is the way he began. He went on to say that he knew that the parishioners were bewildered and that their hearts were aching because sin had crept into their place of communal holiness. Then he transitioned into an explanation of temptation, which morphed naturally enough into a definition of sin. And then he moved into the weakness of the flesh, telling how everybody lusts—what?

The boys were eight and ten at the time. They blinked at the word “lust.” David and I exchanged questioning looks.

“Is it more sinful for a priest to commit adultery than for one of you to do the same?” The priest raised an inquisitive brow, then continued, “More heartrending, perhaps, but we’ve already established that we all sin.”

The man talked about the pitfalls of rampant lust for forty-five minutes. And then he spent another fifteen speaking about mercy and forgiveness and healing.

What I surmised was that this congregation’s priest had had an affair with one of the staff members. Both were married. Both had children. The priest gave up his calling. The woman’s marriage ended in divorce.

Heartrending indeed. And salacious.

In the beginning Sam and Curtis were patient, but after the first half hour, Curtis became censorious. As far as he knew, it was an unbreakable rule that sermons should last no longer than twenty minutes. Also, this was church and church was supposed to be about kindness and doing the right thing, and that guy oughtn’t to have been preaching about sex when there were kids present.

The boys began to fidget. David and I, too, were becoming antsy. We’d been sitting there for an hour and a half and we hadn’t even had communion yet. And with this many people, that could take another half hour. Our little foursome was very tense.

It was time for the offering. Oh dear. This would also take a long time.

When the brass plate came and I passed it to Curtis, he fumbled it. Money and checks went everywhere. And Curtis, mortified, began scrambling around, attempting to pick it all up. But no, I wasn’t having it. I took the plate from my son and handed it over to his father, who passed it on.

Then I stood and signaled my three beloveds, also, to stand; and, bumping against strangers’ knees, we stepped from the pew and moved quickly toward the exit while all eyes followed our progress. This had been a surreal and absurd experience. I was pressing my lips together to keep the laughter from escaping. But alas, sometimes laughter will not be quelled. A giggle became a cackle; then David released a hoot. We were all guffawing loudly as we pushed the doors open and escaped into the sunshine.

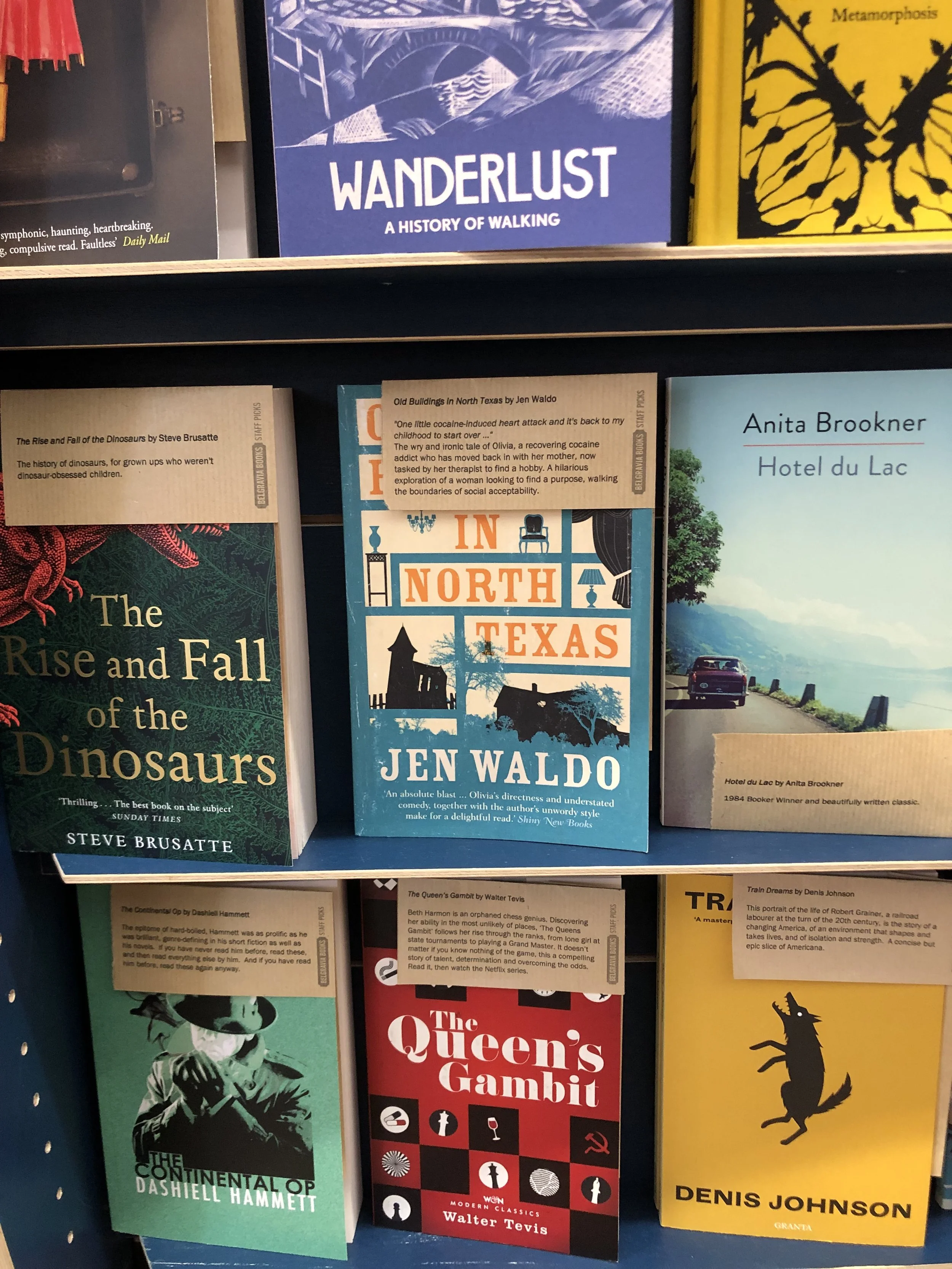

For those who haven’t heard, my novel Old Buildings in North Texas was on the Staff Picks shelf of Belgravia Books in London a while back—a very impressive literary book store. Yay me!