“My mother-in-law broke her hip,” Amy, a Mahjong friend, tells us.

“That’s terrible.” My response is without thought or sincerity. My mind is on the tiles in my rack. What started out as a lovely aroma has rapidly turned into a stink.

“We’ve been expecting it,” Amy continues. “She’s in her late eighties and she falls at least once a week.”

“My, my,” Lucille murmurs. She plucks a tile, looks at it; it’s no use to her and she discards, identifying it—“three bam.”

“Every time it happens, Arnie has to call us to come help get her up. She weighs three hundred pounds.” Arnie, I assume, is the father-in-law. Amy shakes her head despondently, takes the next tile in line, makes an adjustment in her rack as she adds it to her hand, and discards a wind. “And then Arnie, ninety-one years old, hits a deer while he’s following after the ambulance. His car was too damaged for him to continue on, and he’d forgotten to charge his phone, so he was stranded on the side of the road with a dead deer.”

“That’s terrible,” Kendra says, her eyes not moving from her rack as she takes a tile and barely glances at it before tossing it on the table, saying, “North wind.”

“So finally someone driving by figures out that here’s an old man in trouble,” Amy says. “So they stop and offer their cell phone and he calls us and we go pick him up and take him to the hospital to be with Catherine, who, by this time is in a panic because she’s scared to death something happened to him.”

I pick up a one dot, view it sadly, discard it. All I need is a pair of flowers. There are eight of the stupid things. I figured my chances were good. But at this point, five have been discarded. Pairs are tricky: I can’t complete a pair from the discards unless it’s for Mahjong. Amy picks a tile, discards a flower. Damn! Two left, and I need them both. If I can just draw one, at least I’ll have a chance. Kendra draws, discards a four dot. My turn. Be a flower, be a flower, I say in my mind. It’s a two crack.

And still Amy talks.

“And then, while we’re in the emergency room waiting for someone to talk to us about her x-ray, Arnie starts making a fuss about how long it’s taking.” Dismayed, she makes a smacking noise. “Well, his wife is in pain, and he’s frustrated because there’s nothing he can do about it, so he goes out into the corridor and starts stopping random hospital workers, shouting in their faces and waving his arms until someone calls security.”

Kendra discards the seventh flower. My hand is lost. At this point all I can do is try to keep another player from getting what she needs. Kendra and Lucille have enough of their hands exposed so that I know what to avoid discarding. Amy hasn’t exposed anything except the details of her horrible weekend.

“We took him outside and calmed him down, but then he just collapsed in tears. There he was, in Bill’s arms, crying like a baby. He hasn’t spent a night away from his wife for ages, maybe not since they got married over sixty years ago.”

Yes, Amy’s talkative. But it’s not self-centered jabbering. Even now, the story she relates is about someone else’s misery. In our Mahjong group, she knows the names of everybody’s children, and the names of their children’s children. She knows all the women’s health issues and their husbands’ health issues. In fact, so overtly thoughtful is she that I, who, in the best of moods, can only be described as irascible, once asked her how she could be so nice all the time, and she answered, “I love everybody.” And I believed her.

Lucille takes a tile, discards.

“They set her hip with screws and cable. Cable. I’ve never heard of such a thing.” Amy takes her tile, immediately rejects it.

Kendra grabs the next tile. Her lashes flutter as she places it in her rack. She got something she needs. She discards an east wind.

I pull a joker, and immediately thump it in the middle—as jokers can’t be part of a pair, I have no use for the thing—which causes Lucille to emit an unhappy grunt. She could’ve used it.

“And now Arnie’s staying with us,” Amy says. “He’s so worried about Catherine that he can’t sleep or eat. And when we got a call this morning that she’s going into a rehab facility, he started crying again.”

Lucille pulls her tile, discards it.

“Is it really rehab, or is it a nursing home?” I ask. Having witnessed my own mother-in-law’s long decline, I know all about the conveyor belt for elderlies.

“They’re calling it rehab. But we all know she’s never going home again.” She lifts her tile, looks at it, and, perking, announces, “Mahjong.”

My first reaction isn’t generous. I wanted the win. I wanted the tiles to be on my side. Also, Mahjong takes concentration, and she was talking the whole time. Does her mouth work separately from her brain?

Mahjong players speak of "the winds of chance," and "the whimsy of the Mahjong gods." In addition to being capricious, Mahjong is karmic. Because Amy's had a tense few days, Mahjong will be kind. Wiggling with joy and straightening in her chair, she's anxious to move on to her next win. Expediently she collects her winnings and starts shuffling the tiles. She makes Mahjong ten out of thirteen hands (unprecedented!), talking nonstop the whole time.

This pair of flower tiles is taunting me.

Isn't this a beautiful hand? No jokers, and I pulled it all myself. didn't take a single discard from the center. The white dragon and east wind don't belong, though. Oh, for a pair of flowers.

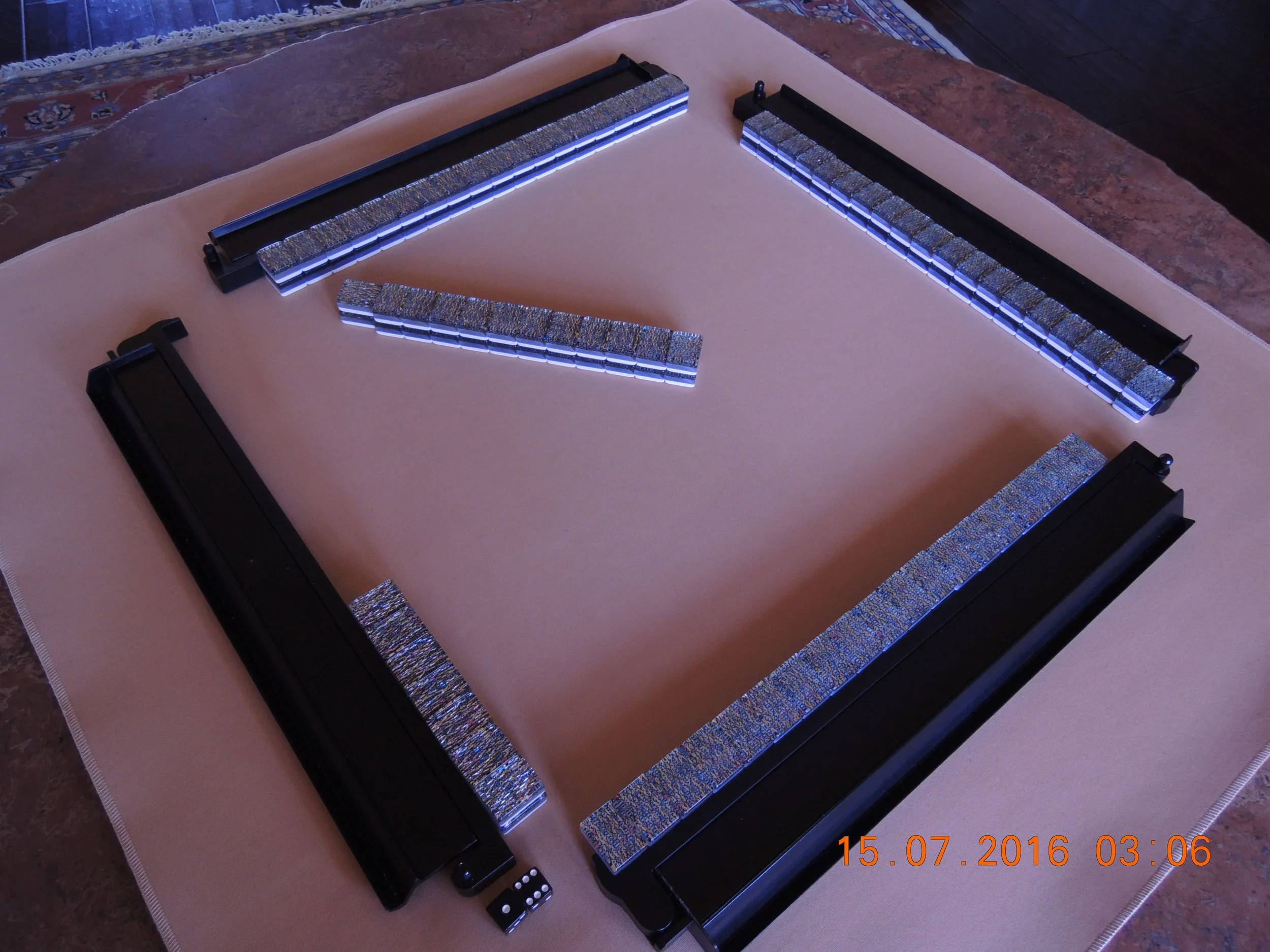

Ready to play? I played with a woman in Singapore who believed that the ends of the walls need touch so the evil spirits can't get in.