We catch the boat in Seward, a small town at the head of Resurrection Bay. We’ve been looking forward to this portion of the trip where we’ll follow the dramatic fjords and perhaps catch sight of whales. A boat this size disappeared about a year ago, and there was speculation, bordering on certainty, that it was taken out by a whale. So, as I am understandably fearful, I share the story with my travel mates, who are unimpressed; they’re more concerned about throwing up than whale danger.

This is the roughest sea I’ve ever traveled. Up, up, up to the crest; then Slam! into the valley of the wave. Repeat a billion times. I don’t tend toward seasickness, so I sadistically enjoy every up and down of it while every one around me moans and turns green. It is, however, disappointing that the heavy fog hinders fjord viewing.

We arrive on a beach and are told that it’s an easy mile-long hike to the Kenai Fjords Glacier Lodge. It’s on this short walk that disaster catches up with David—his hiking boot falls apart! The sole, barely attached at the heel, flops all over the place. Toes are exposed. This couldn’t be more suitably timed, as, when we were packing, David informed me, in a rather pompous tone, that he’s had those boots longer than he’s known me. Thirty-three years. (Well, gee, David, we were going to Alaska. Maybe you should have invested in a new pair.) But all was not lost. A woman gave him a tiny bungee string to hold the shoe together until we got to the lodge; and Dennis, a member of our tour group, offered the extra pair that he’d brought along, just in case they were needed. Whew. Misfortune overcome. This is the sort of thing that seems inconsequential when it happens to someone else, but it’s a big deal when it happens to you. Mortified that his gear fell apart, and sorrowful over the demise of one of his oldest belongings, David mourned the loss for a whole hour. Then he perked up and got on with things, wearing someone else’s shoes.

The lodge is stunning. Nestled in a tidal lagoon, it overlooks Pederson Glacier. The bay is a mirror dotted with floating mounds of white. Otters are everywhere, cute with their playful eyes. Right in front of the dock, a seal’s round head pops up, twinkling eyes visible, then disappears again. It thinks it’s being sneaky. We see you, seal.

Of the three places we’ve stayed, this is the nicest. The cabins are large and, thankfully, have bathrooms. Most importantly, this lodge has a designated drying room, made arid by the hot wind from the generator. As were the other lodges, the location is remote. There is no garbage pick-up. They produce their own power and process their own waste. Every aspect is designed to leave only the tiniest footprint.

Delicious food, charming guides, a nice wine bar, a surplus of equipment in excellent condition—these things are appreciated, but all fade when compared to the breathtaking scenery. I’m sure there are other lodges like this in Alaska, where tourism thrives and the isolated pristine wilderness is the attraction; but in all my travels I have never seen a place as beautiful as this—the jagged gray mountains patched with glaciers that from a distance look insignificant, but grow to massive proportions upon proximate approach. The water, ocean and glacier, the bluest blue. Air so pure that it makes me dizzy. Every once in a while, a great Boom! A part of a glacier has broken off. Echoes for miles. Calving.

We’re kayaking to the Aialik Glacier. We don comical gear—rubber boots, rubber overalls, two rain jackets; and an oddly flared skirt over it all. Plus lifejackets. And then we tromp the mile to the shore, uncomfortable and looking ridiculous in the absurd skirts. During our travels, we’ve combined and split away from other tour groups, and this activity is open to all who are staying at the lodge, but the only guests who’ve elected to come along are the people we started out with, the ones we’ve become quite close to. One by one we squat into our places in the kayaks, encouraging one another and enjoying ourselves. The skirt edge fits tightly over the rim of the seat; and this, we’re told, will keep us dry. By this time, I know better. To be in Alaska is to be wet.

David and I aren’t experienced kayakers. He sits in back, working the rudder as he rows, attempting to control where we go. I’m in front, rowing hard, putting my shoulders into it. But for some reason David can’t keep the bow going straight. We go one way, then the other. This body of water is still; no current, no waves. Maybe the rudder’s broken. As a group, we’re aiming toward a distant island, and the glacier beyond. I’m putting all this effort into gliding forward, yet we’re zigzagging. It’s a waste of energy. So I decide that when we’re not heading where we should be, I’ll stop rowing.

“You can’t keep a beat,” David complains, as though he’s doing everything right back there.

“So says the scientist to the music major,” I tell him. “I’m a human metronome.”

“We’re supposed to row in sync.”

“If you want me to row then keep this thing true. It’s stupid to row in the wrong direction.”

Out of sorts with one another, we continue our efforts in sulky silence. For about three glorious minutes on the outgoing trip, we get it right—flawless, coordinated, advancing quickly in the right direction.

And during this brief spell, I hear Dawn, in a neighboring kayak, say to her son—“Look at David and Jenny. Cooperating, going forward smoothly. Only when you’ve been married for years can you achieve that kind of harmony.”

Harmony. Ha. Sometimes something can look one way when it’s really not that way at all.

We arrive at the base of the massive glacier. With icebergs floating around us, everything is eerily still, silent, enchanted; time stops. We cease rowing and talking, and simply gaze at the magnificence for fifteen minutes or so. Then we complete the circle around the island and zigzag back to our starting point on the shore.

A view of the glacier from the kayak.

Even the best hiking boots don't last forever.

The view from the lodge. Because of the fog, the glacier is barely visible.

View of the lodge from the end of the dock.

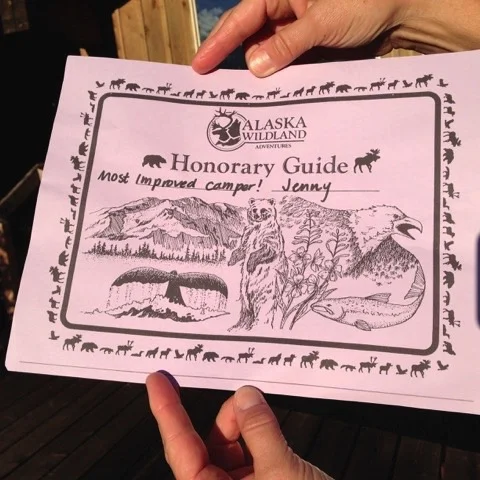

On our last night at the lodge, Elias, our guide, asked us to meet for a "ceremony." Knowing he was going to advise about tipping practices in Alaska, I teased by asking if it would be an awards ceremony. He made this especially for me.